Cabaret! — a way to share stories through song and spoken word, creating a community of audience and performer.

A Brief History: Chicago Black Cabaret

Café concert style cabaret originated in Paris at the end of the 19th Century and was popular in Europe in the early 20th century surviving even into the present. At first, cabarets were by and for artists to share their latest works and to celebrate skills among fellow artists. The art often was experimental and the venues were cheap. Entertainment cost only the price of food and drink. It was not uncommon for the artists to perform for free, with only passing the “hat” as compensation.

About the same time in mid-western America, the conditions for cabaret emerged with the integration of African-American music into popular culture. Ragtime had grown out of the jig piano work in brothels of the vice districts of New Orleans, St. Louis and Chicago. Associated with honky-tonk, jig piano was characterized by self-taught “piano thumpers” who made up for a lack of skill with an over-abundance of expression. Bringing African rhythm to bordellos and saloon concerts the new music went viral. Opposed by mainstream sensibilities, ragtime practically defined a fringe movement.

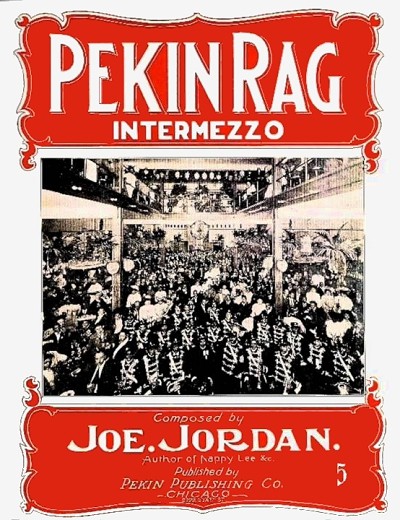

At the turn of the 20th century, ragtime music became successfully monetized with sheet-music sales. It was soon appropriated for the legitimate stage where it crossed over into popular entertainment mostly by and for white America, although, many of its greatest composers and performers were Black.

The sheet music cover seen here was created for Joe Jordan when he directed music for the Pekin Theater Stock Company in Chicago. The Pekin was the first African American theater in America. Cabaret stars Josephine Baker and Bricktop both worked at the Pekin as chorus girls before becoming famous in Paris. In her 1983 autobiography Bricktop remarked “that Montmartre had “as many cafes and dance halls and bordellos as…State Street in Chicago.”

Early ragtime artists converged on the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, but were shut out and consigned to the outskirts of the Midway and to the nearby vice district. The ad hoc saloon concerts or private parties (salon concerts) were the forerunners of Chicago cabaret and were a big hit on the “fringe” of the Fair.

The Haitian Pavillion was the only place in the 1893 World Columbian Exposition where Blacks had a role, thanks to Frederick Douglass’ Haitian ambassadorship. Dunbar’s poetry was read, speeches were made and songs were sung but no ragtime music was played. Fairgoers who wanted to hear the new music found it, along with gambling and prostitution, in Chicago’s red-light district, the Levee.

Ragtime was most impactful in bringing syncopation to popular music. Mainly a solo piano-based form in its classic manifestation, as exemplified by Scott Joplin and his followers, its syncopation soon fostered dance forms which contributed to its global popularity. It is hard not to move to syncopated music. First on the “variety” stage, and later on Broadway, the Cakewalk led the procession of popular dance fads that emerged along with syncopation.

Prior to the dance craze, ragtime was mostly performed as a sporting man’s entertainment in brothels and saloons. Unaccompanied women were stigmatized as prostitutes if they frequented saloon concerts but that changed with the dance craze. Cabaret rooms became a place for men and women to meet for social dancing and to be swept up by each new dance craze—by the turkey trot, the bunny hug, the fox trot and the tango, to name a few. Woman could meet socially for the first time and express themselves without necessarily being suspect. It was modern and daring to be able to drink and socialize in the mixed company of a cabaret.

After the upheaval of the Great War, jazz emerged as the cutting-edge music. Although born from the Black diaspora, the Golden Age of Jazz incubated in Chicago. After the World War I, small jazz clubs were known as cabaret: venues that were already accepted as places to encounter the latest in popular Black music.

Dance clubs flourished and social distinctions caused a split in the purpose of clubs. The well-to-do gravitated to ballrooms and larger dance clubs. The middle and lower classes (and the aficionados) gravitated to the cabaret, where jazz bands were the main feature, while singing and dancing were also presented.

The Dawn of the Golden Age of Chicago Jazz

A landmark occurred at Bill Bottom’s Dreamland Café in Chicago 1921, when clarinetist Lawrence Duhé´s New Orleans Creole Jazz Band with Lil Harden at the piano was re-formed as Joe Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. Oliver went on to recruit jazz artists he had known in New Orleans for his new combo in Chicago including his protégé, Louis Armstrong. The Oliver combo became the house band at Dreamland, and headlined in other clubs like Lincoln Gardens to lead the vanguard of the Golden Age of Chicago Jazz.

In addition to “King” Oliver the Dreamland featured singer Alberta Hunter and a full cabaret show.

The Duhé combo was not a “reading” band but rather a tight improvisational phenom. When they played clubs that were more vaudeville-influenced, they needed a pianist like Hardin who could accompany variety artists. Under King OliverHardin’s leadership famously rose to the occasion.

Joe “King” Oliver seated

During Prohibition the lives of Black artists were further complicated by the influence of organized crime in hospitality. Fortunately the mob found Jazz to be both popular and profitable. Unfortunately the sensation of working for an unjust system may have been all too familiar.

In The Bootleggers: The Story of Chicago’s Prohibition Era, Kenneth Allsop wrote, “When liquored up and pleased, gangsters were lavish with their tips to the jazzmen, but they also indulged in such pranks as flipping lighted cigarettes at the band as it played and occasionally using it for target practice.” “Flying bullets and beatings-up were occupational hazards for jazzmen of that era.”

From 1900 to the 1920s, Chicago enjoyed an explosion of popular culture. Black Chicagoans participated in this entertainment upsurge, but in a separate amusement zone on the Stroll along 35th and State Streets. White skin remained a prerequisite elsewhere for admission to the new, wider public sphere of Chicago’s amusements elsewhere. African Americans found themselves excluded entirely in the most intimate of entertainments or, in the case of theaters, segregated to balconies. They sued theater owners, but their major action was to build their own theaters, saloons, and cabarets, starting with the Pekin, the nation’s first Black-owned theater, opened in 1905 by Robert T. Motts. By the early 1920s, numerous places existed for Black workers to dance or see a show on the Stroll. Among the cabarets and dance halls were the Dreamland Cafe, Lincoln Gardens, the Entertainer’s Cafe, the Sunset, Plantation, and the Apex. For migrants from the South, clubs helped ease the transition between rural mores and city culture.

With the South Side’s cafes and dance halls booming, Chicago was America’s jazz capital during the twenties. Musicians from New Orleans and other parts of the country followed their audiences to the city as part of the “ Great Migration.” King Oliver’s Dixie Syncopators (with Louis Armstrong), Carroll Dickerson’s Orchestra, Earl Hines, Zutty Singleton, Ethel Waters, Alberta Hunter, Bessie Smith, clarinetist Jimmie Noone, and many more played all over the South Side. White slummers bent on losing their inhibitions in “black and tans” soon followed, as did the many white jazzmen who sought to learn the new expressive music from the artists who had created it.

by Lewis A. Erenberg, Entertaining Chicagoans (chicagohistory.org)

Influence of Variety Arts

The history of jazz is well documented elsewhere (as summarized above in Professor Erenberg’s comments), but only in recent years scholars have begun to credit the cross germination between jazz and the existence of thriving Black variety arts. For instance, there was a national Black Vaudeville circuit, Theater Owners Booking Association or T.O.B.A. beginning around 1909. There were also tent shows which toured widely in the summer. Some tent shows were associated with circus side shows and were of high quality musically. Variety entertainers and musicians likely contributed to the programs that were produced in cabaret. Early on classic Blues sung by such artists as Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith and others were in the mix. Many of the Blues singers also performed pop tunes and came to be known more as jazz vocalists, like Ethel Waters and Alberta Hunter.

Opened in 1911 at South State Street near W. 31st Street, It is believed that The Grand Theatre was on the TOBA Black Vaudeville circuit and presented such acts as Bessie Smith, William ‘Bojangles’ Robinson and Ethel Waters. The Grand Theatre was demolished in 1959 to make way for an expansion of the campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT).

Thanks to the works of music historians Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff, in Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music (2002), Ragged but Right: Black Traveling Shows . . . etc. (2007). and The Original Blues: The Emergence of the Blues in African American Vaudeville (2018), we have a better perspective about the personnel and material available to popular Black entertainers in the early 20th century outside of New York.

In his discussion of Edward Komara’s review of the latest volume, Lars Fischer notes: “Abbott and Seroff acknowledge (p. 288), the Indianapolis Freeman was a key newspaper source for their research, but it folded in 1926, leaving documentation of African American theater and music to the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier, and some local weekly papers. In spite of limited resources after 1926, the authors could . . . continue an endless pursuit of the nature of music that is meant to uplift, and not merely entertain, the souls of African Americans.” Reviewed Elsewhere: Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff, eds. The Original Blues: The Emergence of the Blues in African American Vaudeville. | H-Music | H-Net (h-net.org) accessed 01/04/21.

The Chicago Defender obviously admits to and even celebrates civic boosterism, but even recognizing that, it is clear race pride was a major factor in the Chicago black belt culture. It is apparent that the jazz bands knew the value of what they had going which was unique and at the same time most welcoming of the larger world of popular Black entertainment.

Notable variety performers like Williams and Walker, composers and producers like Cole and Johnson reached the big-time with shows and revues in legit theatre on Broadway in New York City and on tour. These “Big Shows” were also major influences on what was performed in clubs. Cabaret producers in Chicago hired specialists like Percy Venable to stage their floor shows to rival what was seen in big-time revues. Some jazz age advertising saw Venable billed more prominently than the band.

At the end of Prohibition. Bronzeville’s entertainment district moved farther south. The Savoy Ballroom at 4733 South Parkway is where high-school drop-out Nathaniel Coles famously challenged his idol Earl Hines to a “battle of the bands” in 1935. Nat won the battle by wowing the crowd with Hine’s difficult signature song “Rosetta.”

In modern times, Chicago is accustomed to receiving its cultural influences from the East as with today’s “Broadway in Chicago.” But with ragtime and jazz, the influence notably flowed in the opposite direction with plenty of cross fertilization. It is remarkable that some think New Orleans music was perfected in Chicago and Chicago Jazz was perfected in New York.

The thriving conditions for cabaret in Chicago played no small part in this history.

Opinion: The Problem with Minstrelsy

For readers wondering why this prominent historic aspect was not addressed above see this addendum.

Select Bibliography

Abbott, Lynn and Seroff, Doug. Ragged but Right: Black Traveling Shows, etc. University Press of Mississippi, Jackson (2007)

Blesh, Rudi and Janis, Harriet. They All Played Ragtime: The True Story of An American Music. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. (1950)

Erenberg, Lewis A. Steppin’ Out: New York Nightlife and the Transformation of American Culture, 1890-1930. The University of Chicago Press; 2nd edition (1984)

Erenberg, Lewis A. Entertaining Chicagoans. Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago History. Chicago Historical Society. (2005)

Gioia, Ted. The History of Jazz. 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, Inc. (2011)

Kenney, William Howland. Chicago Jazz: A Cultural History, 1904-1930. Oxford University Press; First Edition (1993)

Travis, Dempsey. Autobiography of Black Jazz. Urban Research Institute, Inc, Chicago (1983)